The Nevada Short Line Railway was brief in operation, modest in mileage, and ultimately ill-fated. Yet its story captures the ambition, optimism, and volatility that defined Nevada’s early mining and transportation history.

Construction began in 1913 on the three-foot narrow-gauge railroad, the last independent line of its kind built in the state. Though it never stretched more than roughly 12 miles, the route was anything but simple. Climbing over 2,000 feet in elevation, the line incorporated steep grades and switchbacks to navigate the rugged terrain between the Humboldt River Valley and the mining camps of Rochester Canyon.

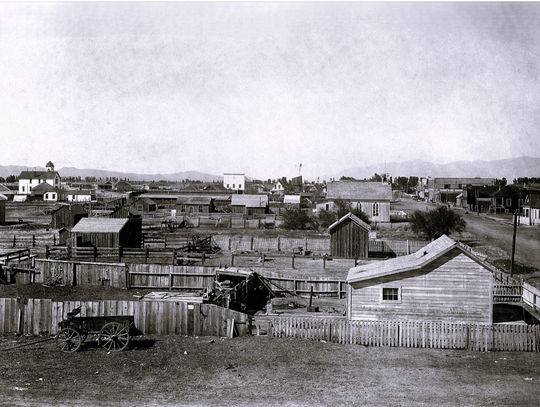

Mining drove the railroad’s creation. Rochester Canyon had seen limited production since the 1860s, but momentum surged in 1912 when Joseph F. Nenzel staked claims on Nenzel Hill, sparking a silver rush. Camps quickly swelled to more than 2,000 people, creating an urgent need to move ore efficiently from the mountains to the valley.

Before the railroad, ore was hauled by wagon along a winding “high line” road through Limerick Canyon—a slow, costly, and inefficient method. Arthur Ashton Codd, controlling the Codd Lease of the Rochester Mines Co., pushed forward with the railroad plan to connect the mines with the Southern Pacific line at Oreana.

Construction moved rapidly. Grading contracts were awarded, equipment was repurposed, and by mid-1913, track laying was nearly complete. The ceremonial final spike, famously made of silver, was later fashioned into a desk paperweight.

Operations, however, were troubled from the start. The first locomotive, gasoline-powered, was prone to breakdowns. Steam engines followed, but windstorms, snow, fires, and frequent derailments kept service inconsistent. A patchwork of secondhand equipment—including a quirky homemade locomotive nicknamed “Mike,” built from a Winton automobile engine—proved ingenious but unreliable.

Despite setbacks, the railroad did operate. Ore moved steadily downhill, empty cars returned uphill, and passenger service briefly ran in January 1915 with two round trips daily to Lower Rochester, signaling cautious optimism.

That optimism was short-lived. Extensions deeper into Rochester Canyon, including a dramatic switchback section, reduced hauling distances but raised costs. Changes in milling practices further cut freight revenue as lighter refined ore replaced bulk shipments. Snowstorms, accidents, legal troubles, and mounting debt compounded financial strain.

Aerial tramways built in 1917 bypassed sections of the railroad, providing more efficient ore transport but rendering the line increasingly obsolete. The final blow came in 1918 when flooding destroyed critical portions of the route. With declining ore traffic, no buyer willing to take on the debt, and mounting damages, the Nevada Short Line Railway was abandoned. By 1920, scrap dealers dismantled the rails, redistributing equipment to other western railroads.

In the end, the Nevada Short Line embodied both the ingenuity and fragility of Nevada’s mining boom era. It fought geography, weather, technology, and economics—and ultimately lost. Yet for a brief moment, it connected mountain camps to the broader world and left an indelible mark on Pershing County history.

Short in miles. Long in story.

Comment

Comments